People often think of the ocean as ‘turbulent’, but we could just as well talk about a structured ocean for ocean currents in fact exhibit an amazing array of patterns, some of which can persist for years if not decades, see my blog ‘spinning disks’. Here I’d like to highlight another class of structured motion, namely how water wends its way through the ocean at depth.

Ever since the publication of the meticulously constructed and artfully drawn north-to-south Atlantic sections by Georg Wüst we’ve had a pretty clear idea of how water masses from the Antarctic and the north spread through the ocean at depth. As our survey tools improved, we could show that how they spread depended upon the shape of the ocean bottom. The very deepest waters – from the Antarctic – could only pass though openings or valleys in deep ocean mountain ranges. North Atlantic deep water from the Nordic Seas spread south preferentially along the western margin of the Atlantic – at 3-4 km depth.

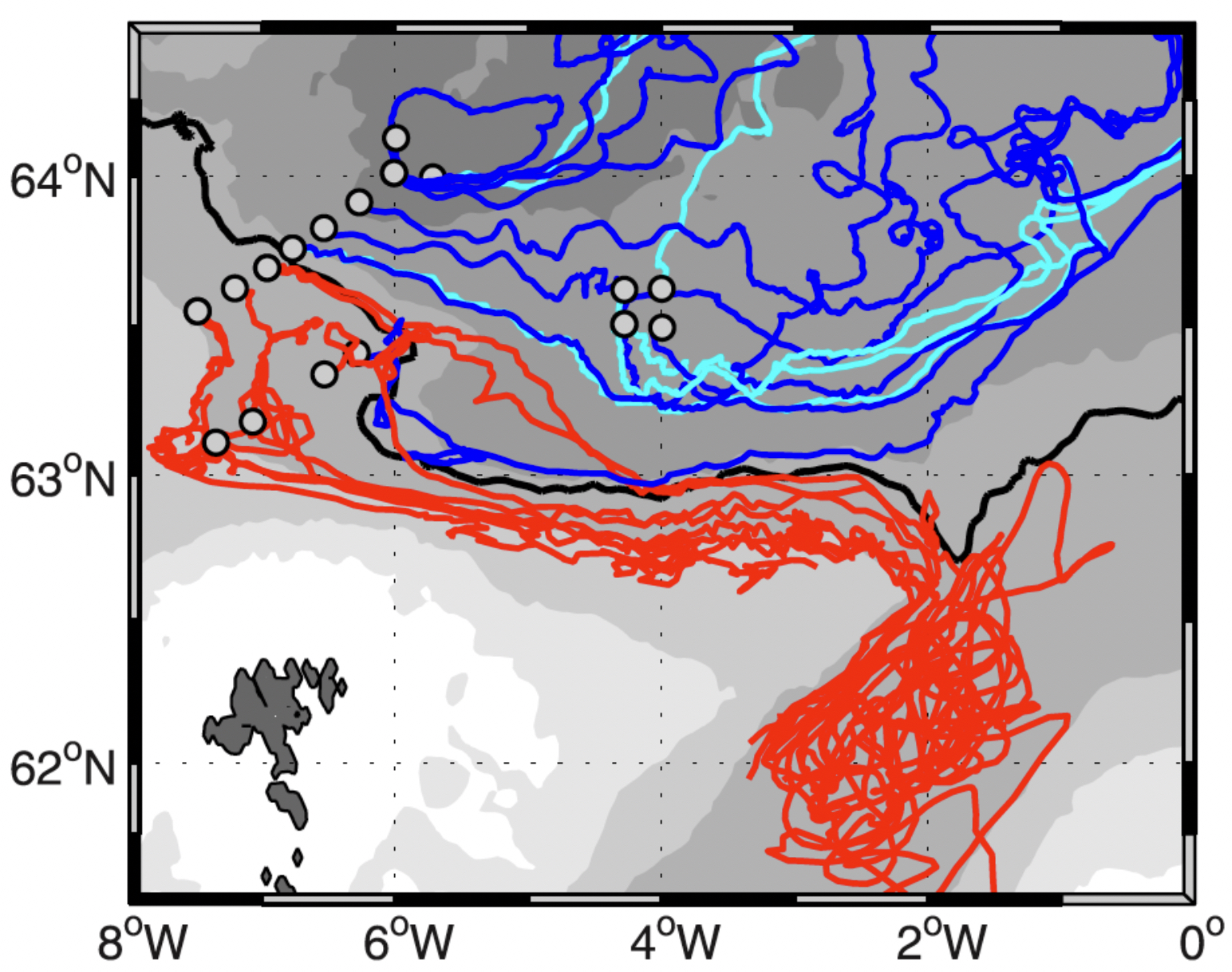

Amazingly, as we zoom in more closely, we find that deep ocean currents exhibit a very strong tendency to flow along constant depth, these lines of constant depth being the ‘tracks’. One can also think of these contours as paths of least resistance. Moving a column of water into shallower or deeper water leads to squeezing or stretching and resulting divergent or convergent motion. This happens when a column of water is forced to change depth but left ‘alone’ it will follow a contour of constant depth. My colleague in Norway, Dr. Henrik Søiland, deployed 22 RAFOS floats at 800 m depth in deep cold water north of the Faroe Islands to see how they might approach the Faroe-Shetland Channel and eventually flow out into the North Atlantic. The findings were dramatic. The figure shows the initial spread of the floats from their deployment just north of the Faroes. Of the total, 14 floats (blue tracks) stay in the Norwegian Sea and 8 (red) turn south into the Faroe Shetland Channel and eventually escape into the North Atlantic. But notice that the blue (and cyan) ones were all released in deep water north of the heavy black line – the 1750 m depth contour – and the red in water to the south, in less deep water. It’s almost deterministic, this depth contour acts like a separatrix setting the ‘downstream’ or ‘future’ fate of deep water streaming east along the Iceland – Faroe ridge. Why do I mention this?

There are vast areas where the ocean bottom is far from flat. Besides mid-ocean ridges, there are fracture zones, subduction zones, volcanoes, and of course there are large flat areas known as abyssal plains. Consider the difference between the latter and an ocean littered with deep ocean volcanoes such as throughout the South Pacific. Deep water will resist flowing up over volcanoes, which means it will tend to work its way along a circuitous path between them. Surely this will increase the impedance (to use an electrical term) to the abyssal circulation? Since constant depth contours are closed around seamounts this also means that water over them will tend to stay trapped there (Taylor-Proudman theorem). This suggests that deep ocean currents may be controlled by bathymetry over a much wider range of scales than just those of ridges and continents. These are very much Lagrangian questions – as illustrated by the above float tracks. To explore these things further it might be instructive to put a cluster of tiny volcanoes in a tank of rotating water, change the rotation rate slightly to set up a gentle mean flow and map out how water works its way through the ‘seamounts’. My guess is water will avoid having to work its way through the cluster – certainly if the cluster as a whole has a closed contour. Perhaps with such an experiment as guide deploy RAFOS floats to conduct a similar study in the volcano-studded South Pacific. Our knowledge of deep water pathways, both spatially and in the mean, is still pretty limited.

Søiland, H., M. Prater, and T. Rossby, 2008. Rigid topographic control of currents in the Nordic Seas. Geophys. Res. Letters, 35, L18607, doi:10.1029/2008GL034846