If you are interested in how neutrally buoyant floats behave in different situations then you’ll find the Prater diagram very instructive. By different situations is meant whether the float is ‘isobaric’ or isopycnal, and whether there is upwelling, vertical and/or lateral diffusion. While not a serious issue the reason for the quotes on isobaric is that it is impossible to design a float to passively remain at constant pressure because temperature or salinity changes will affect water and float density differently. Fortunately, we can turn this fact to our advantage to render a float isopycnal.

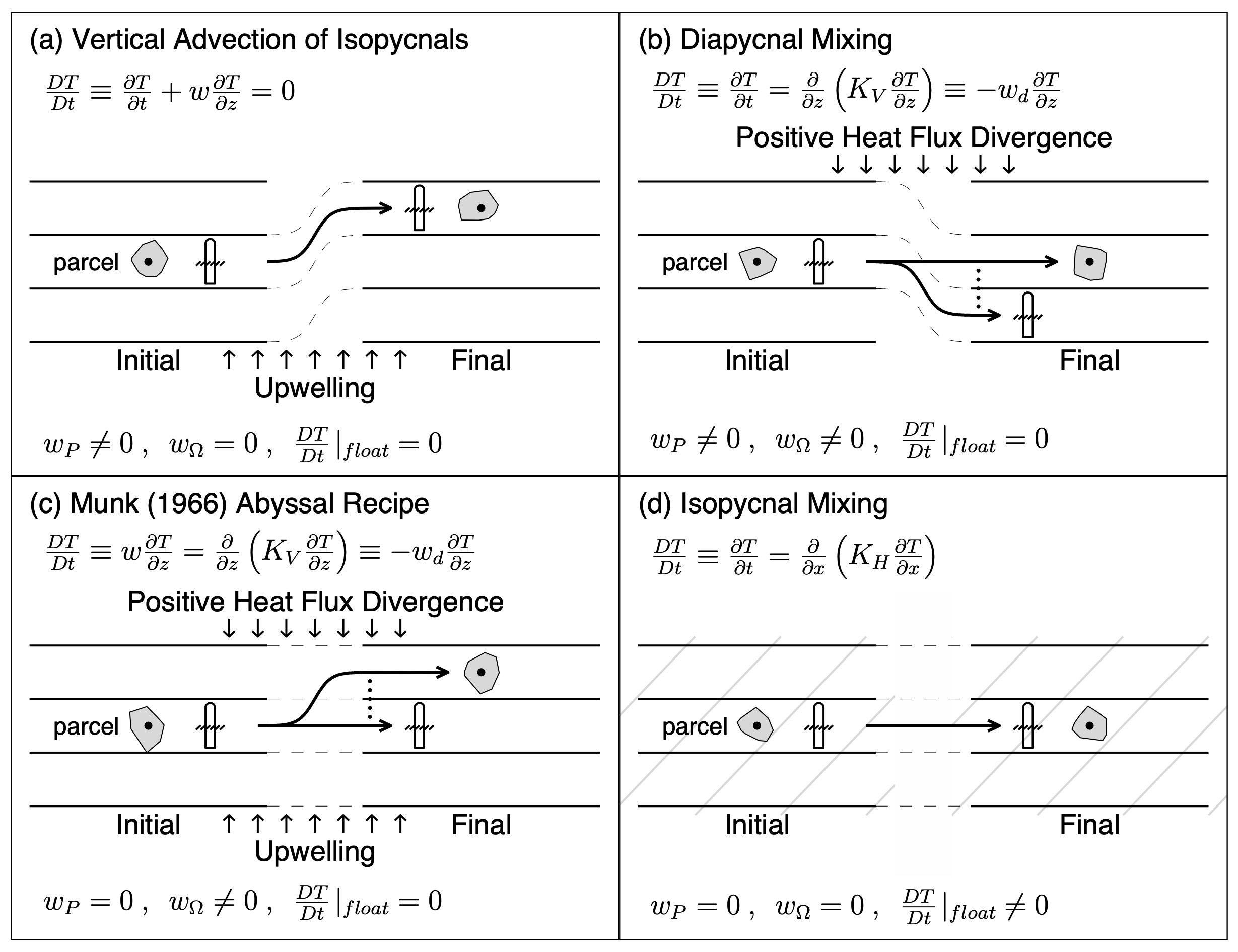

First, salinity can’t affect a float. Second, if the float has a vanishingly small coefficient of thermal expansion (such as with borosilicate glass), it won’t feel temperature either. Which means a neutrally buoyant float will be insensitive to any change in T or S over time. All that remains is ensure that a float will follow the isopycnal as it moves vertically. We do that by giving the float the same compressibility as water so it will expand/contract just as much as the fluid around it due to change in pressure. The Prater diagram shows succinctly how an isopycnal float will response in different scenarios where the starting point is a water parcel and an isopycnal float in stratified water. In the first case (a) an isopycnal float ascends along with the water in the presence of upwelling. The second case (b) considers diffusion of heat from above but no vertical motion: the parcel warms but the float follows the isopycnal downward due to decreasing density. The third case balances the heat divergence with upwelling so the isopycnal remains at constant depth, but the fluid parcel is displaced upward. The last case considers mixing of water of same density but different T/S properties. Density remains constant but temperature changes. As a practical matter cases (b) and (c) apply only near the surface, and (c) specifically to coastal upwelling. When an isopycnal float shoals, crossing a front such as the Gulf Stream say, it will also experience lateral mixing of water with different T/S properties leading to temperature change, a combination of (a) and (d). For a truly isopycnal float, you can back out how salinity must vary as temperature changes. More generally, knowing the equation of state of a float, you can deduce how salinity must have varied from its temperature and pressure record; the float serving as an in-situ hydrometer (Boebel et al., 1995).

Boebel, O., K. L. Schultz Tokos, and W. Zenk (1995). Calculation of salinity from neutrally buoyant RAFOS floats. J. Atmos. Oc. Tech., 12, 923-934. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0426(1995)012<0923:COSFNB>2.0.CO;2