As mentioned in the previous post, and also described in the instrument section, the objective of the free-falling Pegasus instrument was to measure currents as a function of depth. The instrument got its name from the two slender ‘wings’ mounted on opposite sides. Their purpose was to force it to rotate as it sank and rose through the water column so that any tendency for it to ‘kite’ to the side would be averaged out. All this started thanks to phone call from Ants Leetmaa, who wondered if we could develop a technique for probing the vertical structure of the Somali Current. We did so on a very fast schedule (see July 25, 2023). The ‘wings’ led Ants to call the instrument Pegasus and we loved it. Ants was an excellent scientist with a searching mind, first as a sea-going oceanographer, and later taking the initiative to develop models for climate studies. He was a very kind-hearted and generous person; I remember him fondly.

By the Pegasus files I mean the data we collected from our bi-monthly sections we took of velocity across the Gulf Stream between 1980 and 1983 (see my post July 25, 2023). While numerous hydrographic sections have been taken across the Gulf Stream starting in the 1930s, the Pegasus program was the first one to take sections of the velocity field. A major objective was to determine volume transport without having to depend upon geostrophy and an assumed level of no motion. The findings were reported in Halkin and Rossby (1985).

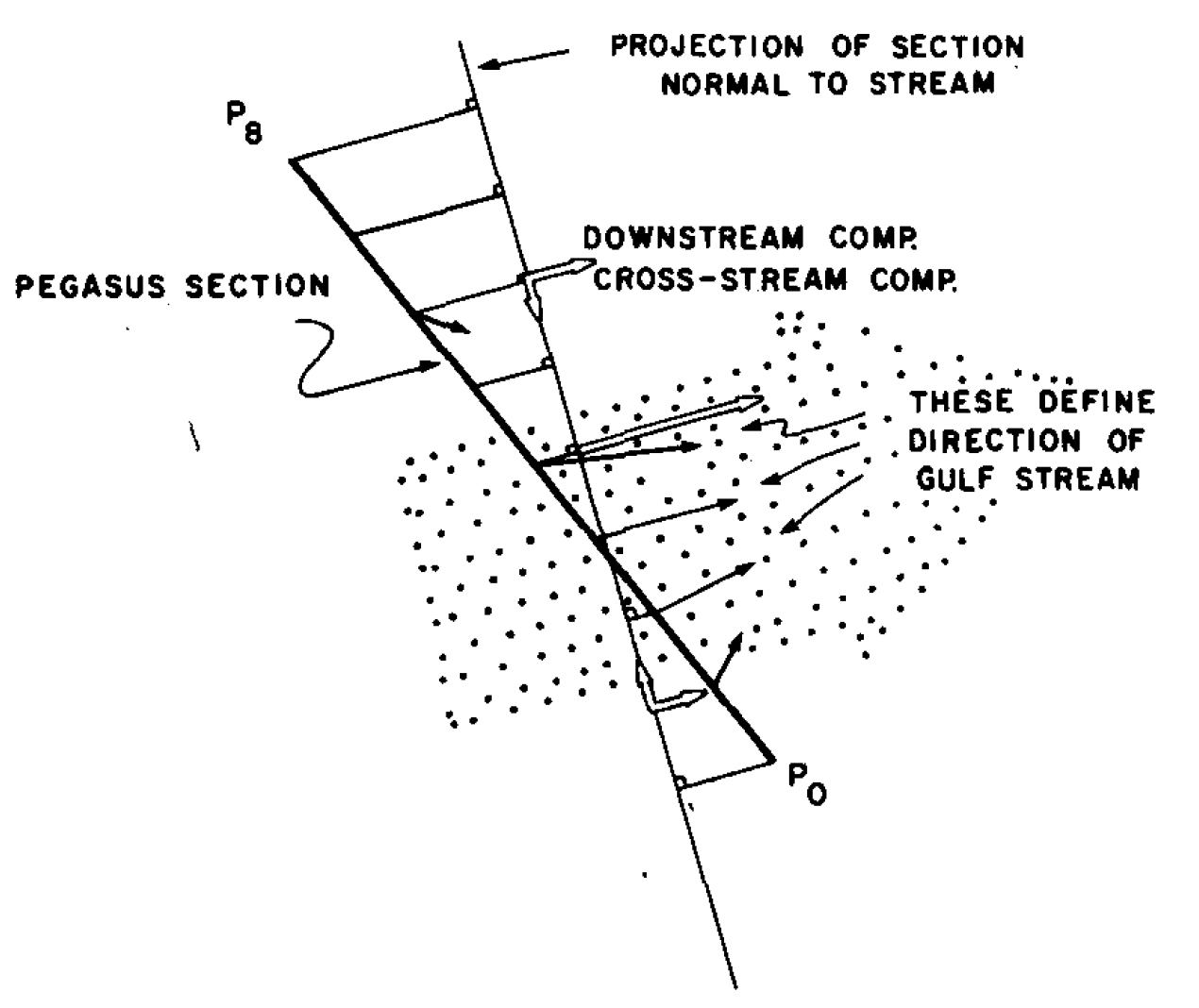

A unique aspect of the project was to use the vector information to remap the sections into what we call stream or natural components where we use the maximum velocity vectors to define a downstream and a cross-stream direction. This simple transformation of the data revealed a striking uniformity of the width and the strength of the current. The nine sites (P0-P8) along the heavy black line in the figure show where the Pegasus velocity profiles were obtained. The thin black arrows indicate observed vectors while the open vectors indicate their rotation into stream coordinate system defined by the thin black line.

This transformation showed that most of the eddy kinetic energy (EKE) associated with the Gulf Stream was caused by the shifting position and direction of the current. Viewed in stream coordinates the Gulf Stream looked surprisingly ‘stiff’ in terms of shape and size. This is no doubt a universal property of strong baroclinic currents. These data are over 40 years old, but they are still useful. Please contact me if you are interested in a copy.

Years later (2004-2014), a program called Line W took a series of sections across the Gulf Stream about 4° longitude farther east. The focus of Line W was on the Slope Sea, but several of the sections extended south across the current, each consisting of a set of surface-to-bottom casts of high-quality velocity, temperature, and salinity, beautiful data set. I wonder what a comparative study might tell us. While Line W is more recent, the bigger difference is that it is located where the current meanders far more widely.

Having said that, it is a bit shocking to realize that Pegasus and Line W data sets are to my knowledge the only systematic studies of the Gulf Stream velocity field from the surface down. We have deployed moorings that measure currents at various depths. These give us excellent temporal information, but the high cost of these point measurements makes it difficult to get the spatial coverage one would like. This is a major problem in physical oceanography. As mentioned in several posts, we have started to address this by measuring currents from MM-vessels in regular traffic with roughly 1 km horizontal and 20 m vertical resolution, and with a temporal resolution set by the vessel’s schedule. That’s the good news. The sad news is that at best we can only reach to 1-1.5 km depths. Most of the ocean and that includes the deep western boundary currents is still beyond reach. We can and need to do much better. Believe it or not, it is far easier to resolve currents at depth than the temperature and salinity fields.

Halkin, D. and H.T. Rossby (1985). The Structure and transport of the Gulf Stream at 73oW. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 15, 1439-1452.