The reason acoustic Doppler current profilers (ADCP) work, whether on moorings or on ships, is thanks to the kind cooperation of zooplankton and fish populations that inhabit the ocean. These little fellows echo back the acoustic signals emitted from the ADCP, and it is from the Doppler shift in frequency of the echo one can determine the relative velocity between the instrument and the zooplankton. But here’s the thing, besides measuring the Doppler shift, the strength of the received echo is also recorded, this is a huge cache of information we pay little attention to (or don’t know how to use). But, for now at least, they allow for pretty pictures, here’s a wonderful example.

The container vessel Nuka Arctica operates on a 3-week schedule between Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, and Aalborg in Denmark. On her east-to-west transits she sails along a great circle path across the subpolar North Atlantic between Scotland and Cape Farewell. In the early years she was equipped with a 150 kHz ADCP that sometimes could reach to 400 m depth thanks to the high concentrations of backscatterers.

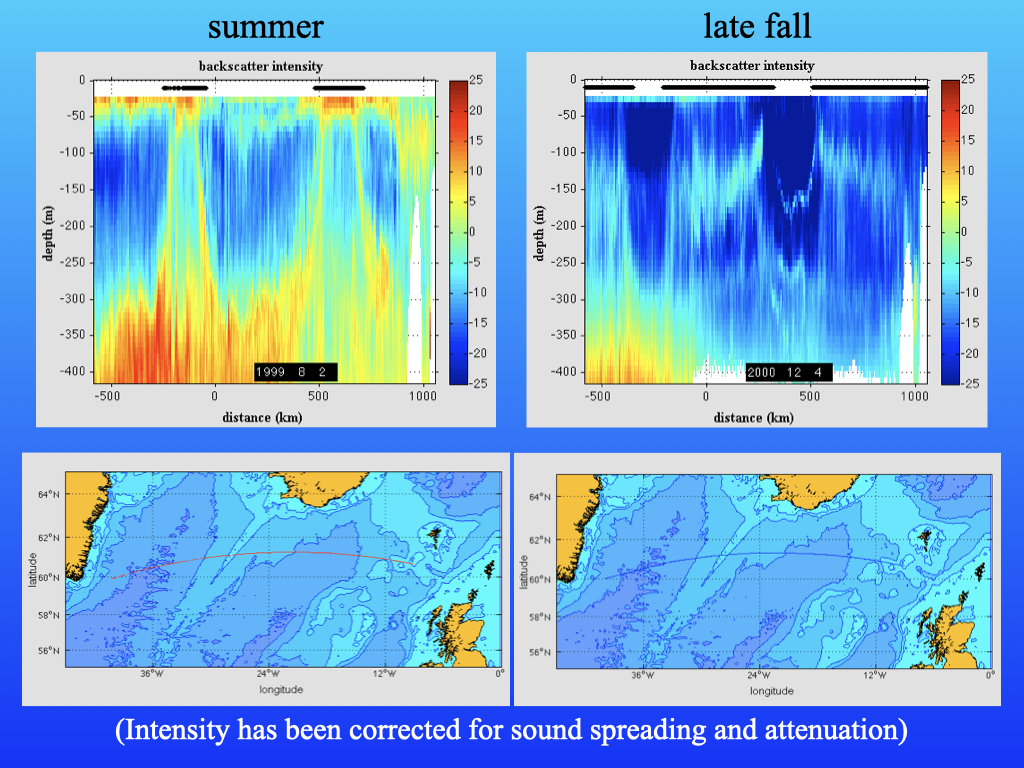

The attached figure shows a summer and a late fall crossing from east to west. The lower panels show the vessel tracks –virtually the same great circle route for both crossings. The upper panels show backscatter strength. The plotted intensity has been corrected for signal loss due to spreading and attenuation. While we have no information on absolute signal intensity, the instrument is stable and gain settings are left unchanged so differences between summer and fall (color scale in decibels) reflect real changes in the ocean. The black lines at the top of the panels indicate when the sun is below the horizon: nights are short in summer and long in winter.

While this is well-known stuff, I still amaze at how the zooplankton (and other creatures) rise to the surface to seek food during the night. The rapid change in depth at dawn and dusk of these tiny creatures is incredible. Distances are in km from the axis of the Reykjanes Ridge. These are snapshots. To my knowledge there has been no attempt to conduct a systematic study of these distributions – as a function of time of day, season, and of location (Irminger Sea vs. Iceland Basin). Note the higher backscatter concentrations at depth in the Irminger Sea; this remains true in winter as well. The vastly lower backscatter intensities in winter presumably reflect the loss of zooplankton and only the fish (mainly myctophids?) remain. Is this correct, I’d be happy to host a guest blog on this. The depth variations during summer daylight may reflect varying cloud cover (we should include solar irradiance in the measurement program!). It’s tempting to suspect that some of the spatial variability (local maxima or minima) might be related to coherent eddies acting like bottles preventing mixing and dispersal?

Given that the ADCP is a very stable instrument, a detailed study of these distributions might be instructive (we have over 3 years with the 150 kHz and similarly with a 75 kHz ADCP). I constantly get the feeling there is a lot of both dynamical and biological information here. In the next blog post I’ll zoom in on the summer transect.

Here’s an excellent read:

Sidebar 2: ACOUSTIC BACKSCATTER PATTERNS by Jaime Palter, Lauren Cook, Afonso Monteiro Gonçalves Neto, Sarah Nickford, and Daniele Bianchi. Page 91 in the September 2019 issue of the TOS magazine Oceanography.