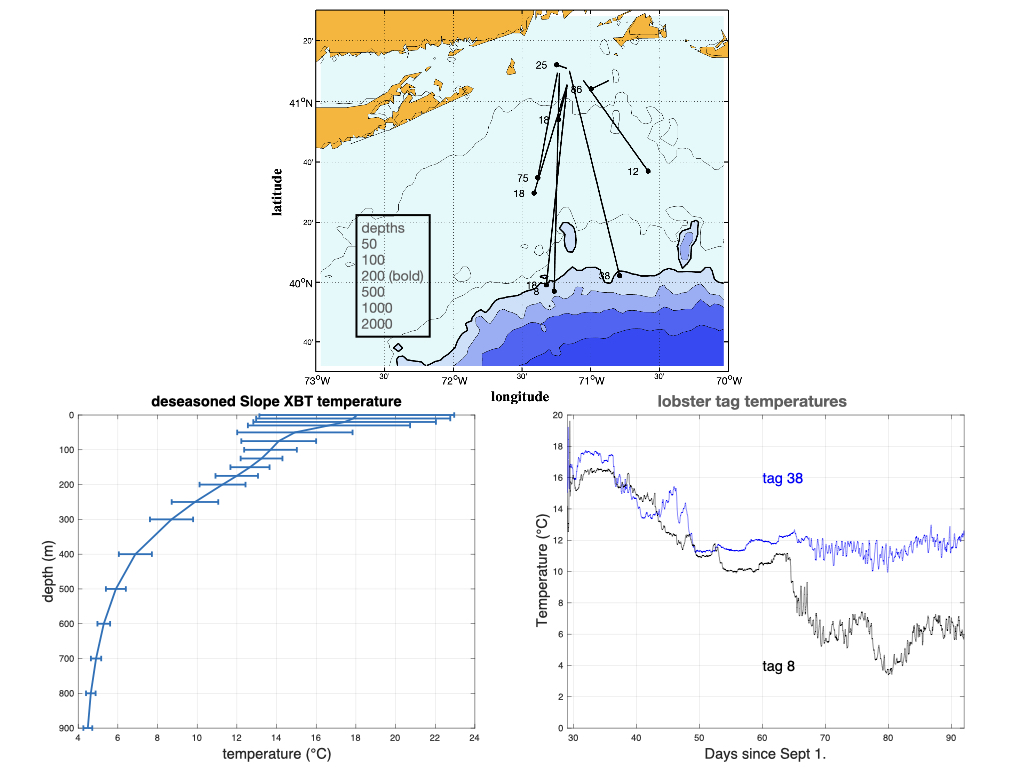

A year ago (Sept. 18, 2023) I mentioned how tagged lobsters recorded some curious temperature variations on the continental slope. The lobsters had been released roughly 20 km east of Block Island. Of the 32 tags released 8 were recovered; their displacement vectors show how far they wandered; three of them 120 km to edge of the shelf and beyond. Sadly, the tags weren’t tracked as planned, but the fishermen logged where the tagged lobsters were caught.

Three of these fellows didn’t waste any time, see map below. Tags 8 and 38 show that they arrived at shelf edge roughly 30 days after release, that is nearly 4 km/day! Lobster #8 went down the slope to ~6°C temperatures or equivalently ~500 m depth. The standard deviations in temperature in the slope waters (see plot below) suggest that the temperature profile can heave up and down a good 100 m. For the first 30+ days after release the temperature records reveal a mostly smooth rather monotonic rate of cooling. Suddenly, starting at day 66 (tag 8) and 68 (tag 38) the tags record high-frequency fluctuations with a roughly 1°C peak-to-peak amplitude with a very roughly 12-hour dominant period, suggestive of an internal tide. In addition, the records reveal a broad peak at days 75 and 85 and minima at days 70 and 80. But if these are internal tides, why are they so irregular, and why did they ‘suddenly turn on’?

As the open ocean tide approaches a continental slope (at ~200 ms-1 speed), the near surface water readily slides onto the continental shelf while water below shelf depth is blocked by the continental slope forcing it up and down the slope, generating in effect an internal tide. These propagate very slowly (in the open ocean at roughly 2 ms-1 velocity, roughly 1/100th speed of the surface tide). Because of this, the internal tide rapidly loses coherence due to currents that distort it, and by the complex shapes of the continental slope inducing internal tides at other sites with different vertical structure. The speed of the internal tide may slow in shoaling depths. If the speed is less than the strength of the current at the slope, then the internal tide will be arrested. If the current changes direction, the tide can progress up or along the slope. I suspect that is what happened around day 66: the background flow along the slope changed in such a way as to allow the internal tide to proceed up the slope (tag 38 is warmer and thus farther up the slope).

If another study with acoustically-tracked tags were to take place, I like to think that just like last time a goodly number of them will work their way south to and down the continental slope giving us a broad-based window into internal tide generation and mixing. A few deployed current meters would give us a handle on motions induced by the internal tide along the slope; when they are or aren’t arrested by the background flow and perhaps how they break. The fact that the temperature variations are far from periodic points to Doppler shifting by the currents, internal wave breaking and chaotic motion along the bottom, processes that will lead to enhanced diapycnal (i.e., vertical) mixing. Indeed, most diapycnal mixing in the ocean is thought to occur along sloping bottoms, not in the open ocean. The rather messy temperature records from these two lobsters may be examples of that. If you are interested in taking a closer look at these data, please don’t hesitate to contact me!