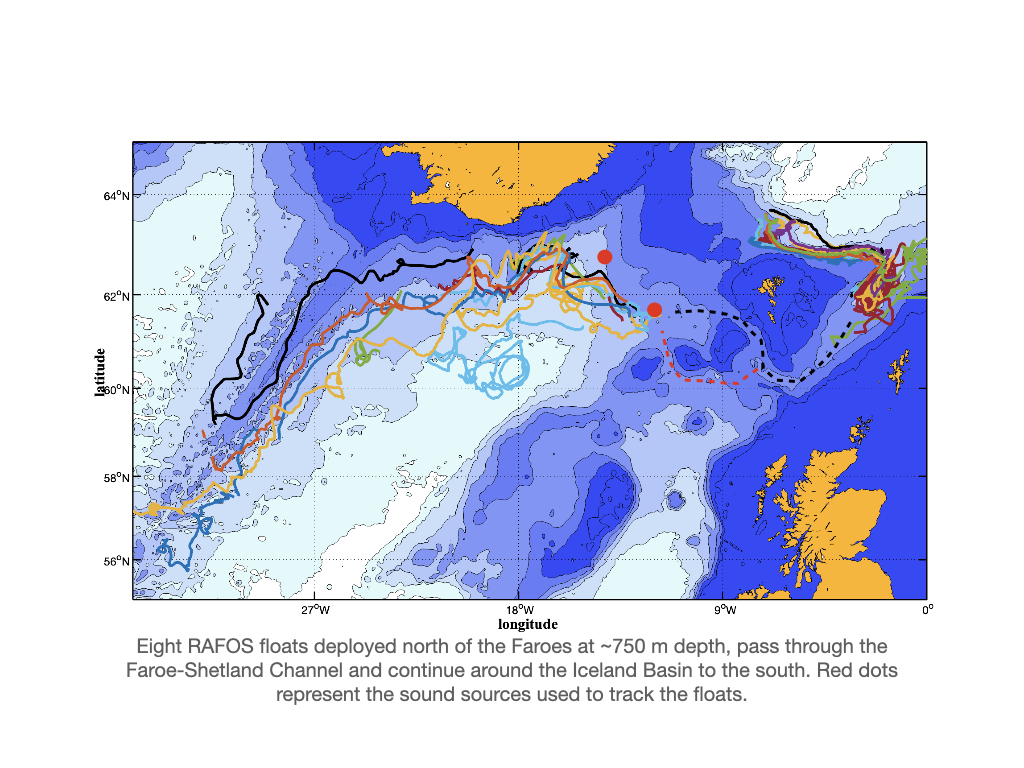

Two years ago, I wrote a post called Tracks in the sea where I showed the incredibly tight control bathymetry exerted on the movement of RAFOS floats deployed on the northern slope of the Iceland – Faroe ridge. The floats, deployed by Dr. Henrik Søiland (Bergen, Norway), were ballasted to drift at about 700 - 800 m depth. The floats in waters deeper than 1750 m (14 floats) turned northeast into the Norwegian Sea while 8 floats deployed in shallower water without fail turned south into the Faroe-Shetland Channel (see the figure in the Dec 9, 2023 post). But I didn’t mention what happened to those floats…

They all wend their way south through the Faroe-Shetland Channel and emerge into the Iceland Basin via the Faroe Bank Channel just above the 800 m sill depth. The warmer, less dense Iceland Basin water caused the floats to sink from ~750 m and -0.5°C to roughly 900 m and 4-6°C temperatures. The floats were ‘out of view’ for ~50 days for an 8 cm/s average speed through the channel indicated by the black dashed line in the figure. The pressure record shows 3-4 floats exhibited a huge 200 m shoaling to ~600 m, the sill depth of the Sir Wyville Thomson Ridge, so is it possible some of these could have left (‘sucked out of’) the channel that way (indicated by the red dashed line)? We know some water leaves the channel that way. Perhaps, but I think it more likely that as the overflow water accelerates into the narrowing Faroe Bank Channel, it slopes higher up on the Faroe side before plunging into the deep Iceland Basin. We had two sound sources in the Iceland Basin so as soon as the floats began hearing the sources tracking could resume. The attached figure shows their subsequent movements. They reveal the substantial constraint topography imposes on the cyclonic circulation around the basin.

Notice their meandering along the southern Iceland slope – why is it that from east to west they first execute a clockwise path contrary to the local bathymetry near the NW sound source, and then an anti-clockwise and clockwise meander following topography? Perhaps it’s just a coincidence, but I suspect not.

As the floats drift 400-500-600 km SW along the eastern slope of the Reykjanes Ridge, it is conspicuous how topographic control suppresses lateral eddy motions such that their trajectories barely cross each other. Curious how the black track crosses the RR and drifts south on the other side. While this may seem implausible, I have absolutely no reason to think tracking (acoustic timing) errors could put the track that far off to the west.

The anticyclonic looper near 60°N 20°W is just north of the famous Prime eddy, a localized area of curiously high eddy kinetic energy (see Jan. 25, 2024).

The main point of the figure is that bathymetry exerts considerable control on the movements of water below the main thermocline. It makes you realize that the deep ocean is far more structured or organized than is the upper ocean. What does this tell us about allowable pathways for deep water transport? Perhaps all transport is along slopes and bottom gradients while the flat ocean interiors are quiescent and ‘maintained’ through mesoscale stirring and mixing? I don’t know, but the good news is that with Lagrangian techniques we can address these questions because with floats we can study arbitrarily quiet oceans. Much to learn!