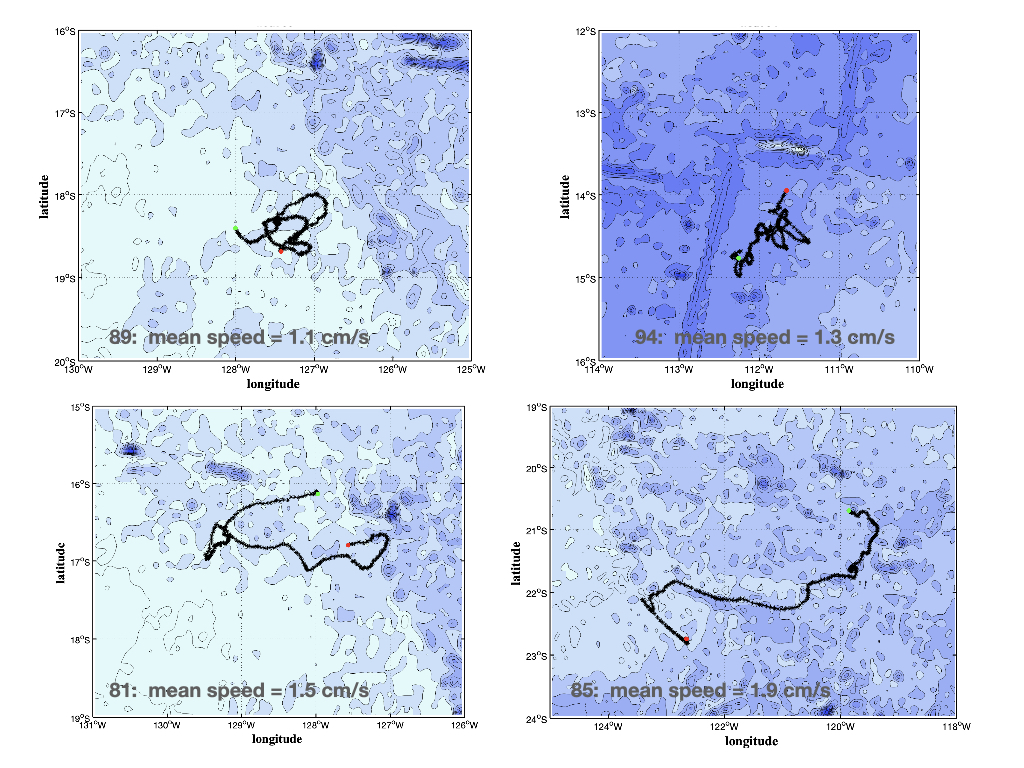

As noted in the previous post, the RAFOS floats we deployed in the He-3 plume (Lupton and Craig, 1981) did not perform as planned. While almost all of them surfaced according to schedule, only eleven of the 48 floats telemetered their data, with the majority of transmitting only scattered subsets, or no data at all. It was very discouraging. Nonetheless, the temperature and pressure records from these various subsets showed that all but three floats settled at their intended depth, around 2500 m depth. We could also get a measure of eddy activity from the available trajectory data. Take a look, it sure is quiet!

The figure shows the movements of four floats. Over their 18-month drift they might move a degree or three of longitude, but not in latitude. The mean speed of the floats is not much than a cm/s over the 18 months. In the previous post we saw how floats over the EPR move very little to the north. It is easy to imagine that the mountainous topography of the ridge imposes a form drag on the overlying water column. The mean and eddy kinetic energy of the eleven tracked drifters 0.2 and 1.3 cm2/s2, resp. (The MKE of all 39 drifter vectors in the previous post is even smaller, ~0.02 cm2/s2, no doubt due to the many slow drifters on the EPR.) Despite a vast He-3 plume driven by hot water vented from the EPR (Hautala and Riser, 1992) these are quiet waters. Indeed, that is why the plume eists - an elevated eddy activity would disperse the tracer.

The decorrelation time of u and v for the tracked floats is 20-30 days (but with large spread to longer time scales). This helps explain why the 18-month displacement vectors are useful: they average over many eddy time scales. There are of course longer time scales as well, which is why it is essential to deploy floats in numbers as ensemble-averaging smooths out eddy activity even further. An important conclusion we can draw from this is that if our primary interest is in mean flow, then we can forego the acoustic tracking and get mean velocity from the movement of the cluster for that period and region,and a measure of eddy activity from the spread of the vectors. The point is that eliminating the acoustics reduces costs enormously and opens opportunities to study deep ocean movements on time scales that have been out of reach until now. Even the best hydrography and altimetry do not have the skill to estimate deep ocean currents with useful accuracy, whereas clusters of deep drifters do.

Another way to appreciate these numbers might be to ask how long it would take to traverse the Pacific at 3 mm/s (the mean speed of the Helios floats). The equatorial size of the Pacific is ~20,000 km or 2e7 m. Dividing that by 0.003 m/s gives us ~200 years, a time scale approaching that of the meridional overturning circulation. I didn’t realize it at the time, but this suggests that with appropriately-sized clusters of deep drifters we have a cost-effective tool with which to accurately determine abyssal flow patterns. This is not a trivial point for we all know how devilishly difficult it is to pin down and quantify the deep ocean circulation.

Lupton, J. and H. Craig, 1981. A major He-3 source at 15°S on the East Pacific Rise. Science, 214,13-18.

Hautala, S. and S. Riser, 1993. A non-conservative beta-spiral determination of the deep circulation in the eastern South Pacific. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 23, 1975-2000.