How oceanography has evolved! Go into any marine library and you will see shelves lined with of tomes of books on the major oceanic expeditions of the past. The Challenger expedition is no doubt the best-known one, but you will also find volumes on major expeditions organized by scientists and explorers in the UK, Germany, France, and the Scandinavian countries. These were in large measure voyages of discovery, charting the patterns of temperature across the oceans, life in them, and what the ocean bottom looked like. As new chemical analysis techniques came along at the start of the 20-century expeditions could also map salinity and oxygen. Novel coring techniques gave us a window into past climates as recorded in ocean bottom sediments.

Today, as we become increasingly aware of the fundamental role the oceans play in the climate of our planet, we need to know how these properties, especially heat, vary across space and time, either in response to or in causing climate change, both regionally and globally. Understanding the present and the past may help us better see how the ocean will trend in the future. This is a huge challenge.

Much has been written in recent years about how the AMOC is slowing and what this will mean to the climate of Europe. The curious thing is that virtually all of these assertions are inferential, many of them based on the bizarre absence of ocean warming south of Greenland (what is known as the warming hole). Contrast that with programs that measure the strength of the AMOC, whether the RAPID program at 26°N, the OSNAP program at ~59°N, or the long-running Oleander program between Bermuda and New Jersey. All three of these show variations in AMOC transport from year to year, but none of them show any trend on the longest time scales of observation. The variations are regional in response to the action of local winds; they do not suggest a change in the meridional overturning. Similarly, direct measurements of water entering and leaving the Nordic Seas reveal no evident trend over the recent decades of direct measurement. This exchange has an even greater relevance to European climate.

Early this year I had written a post about state vs. action, state being the condition of the ocean at the time of observation, and action what the ocean is doing at the time of observation – they complement each other. But I neglected to mention that they are out of phase with each other. Simply put, any change in state requires some form of action, whether vertically through air-sea exchange, or laterally through changes in circulation.

A slow-down of the AMOC means less transport of heat to the north. Today, thanks to our ability to scan currents at high horizontal resolution, we can measure directly the volume of water being transported. Couple this with temperature and salinity and we can also estimate heat and freshwater fluxes. This is the beauty of measuring currents; they can give us a heads-up on future changes in state. But this is only possible through sustained observation. This is fundamentally different from the expeditionary science approach that characterizes sea-going research today. We need to recognize that sustained observation is not business as usual, merely stretched out in time; it requires a fundamental shift in our thinking. The global Argo array is an excellent example of a commitment to sustained observation of the state of the ocean.

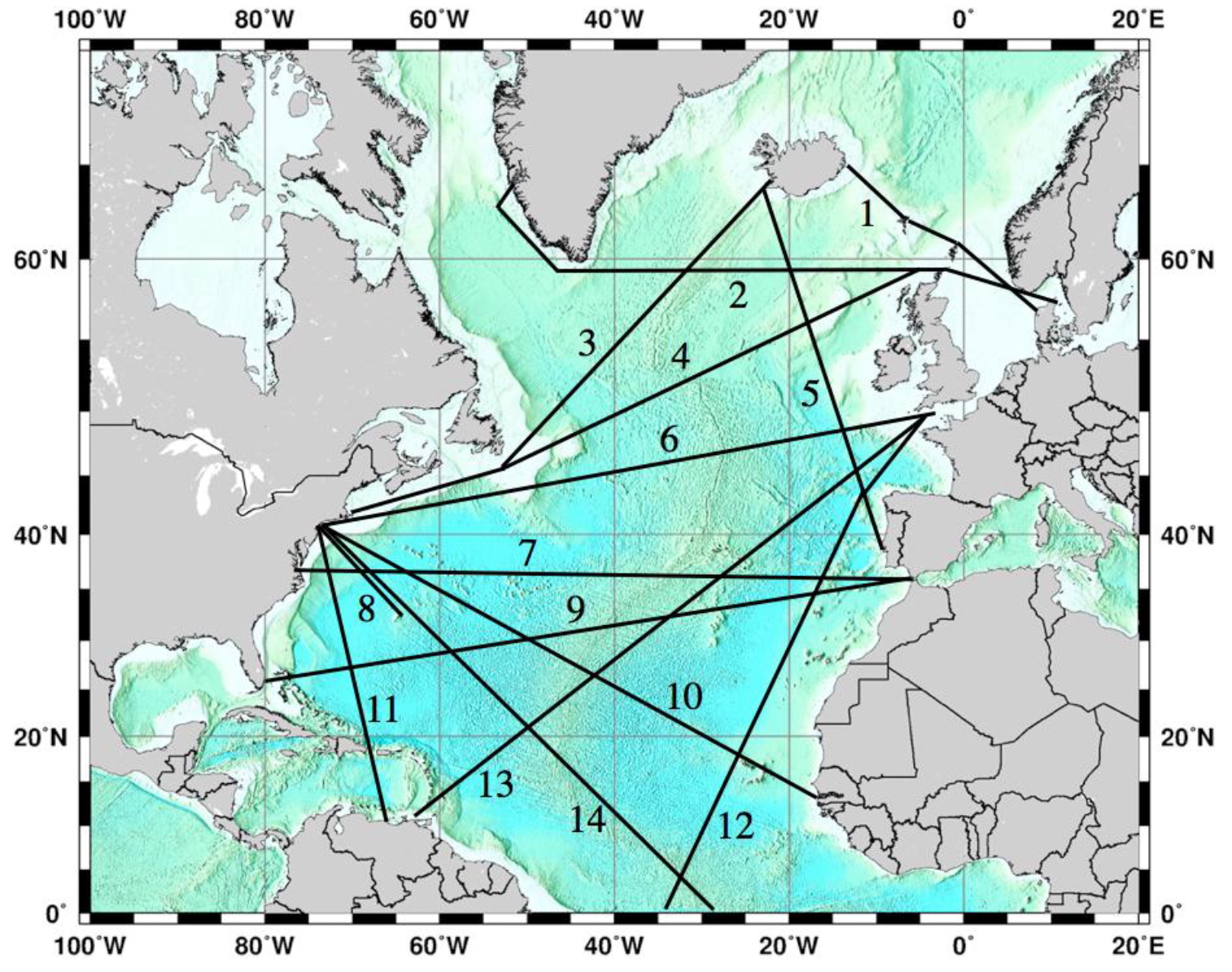

I would like to suggest that a similar commitment be made to track ocean currents and transports along select routes. This can be done very cost-effectively by partnering with the merchant marine who we know from experience is willing to help. The idea is simple: equip MM-vessels in regular traffic with instruments that can profile currents to great depths at high horizontal resolution. All vessels would be equipped with a full suite of weather sensors. The map shows what we had in mind when we wrote the 2012 OceanScope report.

The northern routes would pay close attention to AMOC variability. XBTs and resolved velocity profiles will keep track of mixed layer response to buoyancy fluxes. The low latitude lines would focus more on ocean response to winds. Measuring currents and winds together may lead to new insights into how they are coupled. Simply put, sustained measurements on MM-vessels will give us degrees of freedom we can’t obtain with research vessels.

The Oleander link below describes what might be viewed as a model for future MM-based ocean observatories.

OceanScope report (2012): https://scor-int.org/Publications/OceanScope_Final_report.pdf

Oleander model: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27374569?seq=1